Tableaux

Jeff Wall (b 1946)

Wall describes his work as “cinematographic” re-creations of everyday moments he has witnessed, but did not photograph at the time. “To not photograph,” he says, “gives a certain freedom to then re-create or reshape what I saw.” He takes months to stage and direct each of his “occurrences”. Over the years, they have moved away from the dramatic towards the more quiet and quotidian and, since 2006, he has exhibited prints rather than back-lit transparencies which he was renowned for.

Re-creating images from memory is crucial to Wall’s practice – perhaps because it flies in the face of the tradition of photography as an act of instant witnessing.

“Something lingers in me until I have to remake it from memory to capture why it fascinates me,” he says. “Not photographing gives me imaginative freedom that is crucial to the making of art. That, in fact, is what art is about – the freedom to do what we want.”

One thing that Wall knew for certain when he took up the profession in the late 1970s is that he would not become a photojournalist hunter. Educated as an art historian, he aspired instead to make photographs that could be constructed and experienced the way paintings are. “Most photographs cannot get looked at very often,” . “They get exhausted. Great photographers have done it on the fly. It doesn’t happen that often. I just wasn’t interested in doing that. I didn’t want to spend my time running around trying to find an event that could be made into a picture that would be good.” He also disliked the way photographs were typically exhibited as small prints. “I don’t like the traditional 8 by 10,” he said. “They were done that size as displays for prints to run in books. It’s too shrunken, too compressed. When you’re making things to go on a wall, as I do, that seems too small.” The art that he liked best, from the full-length portraits of Velázquez and Manet to the drip paintings of Jackson Pollock and the floor pieces of Carl Andre, engaged the viewer on a lifelike human scale. They could be walked up to (or, in Andre’s case, onto) and moved away from. They held their own, on a wall or in a room. “If painting can be that scale and be effective, then a photograph ought to be effective at that size, too,” he concluded.

Research

Accessed 12/11/2019

https://www.itsnicethat.com/features/jeff-wall-in-conversation-photography-270819

https://www.theartstory.org/artist/wall-jeff/

https://www.ft.com/content/0d1b7d46-9223-11e9-b7ea-60e35ef678d2

https://www.bjp-online.com/2019/09/any-answers-jeff-wall/

Philip-Lorca diCorcia (b.1951)

Philip-Lorca diCorcia first made headlines in 2007 when he was sued by Erno Nussenzweig, who objected to his portrait being displayed without his permission in a New York gallery. For his series called ‘Heads’, DiCorcia attached a strobe light to scaffolding in New York’s Times Square and positioned a hidden camera nearby to shoot people as they walked beneath. Nessenzweig was one of those unsuspecting subjects. He lost the court case and DiCorcias’s melancholy street portrait of him is one of several hauntingly powerful images.

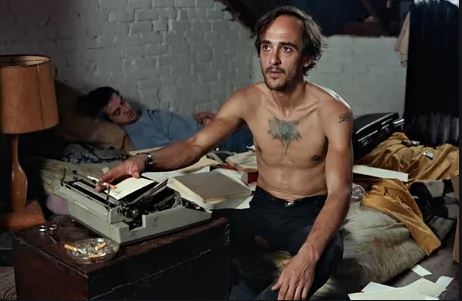

The Heads shots came six years after another – Hustlers, where DiCorcia cruised a strip of LA’s Santa Monica Boulevard where rent boys worked, and offered to shoot their portraits for the same hourly rate they charged for sex. In the same vein to those of Wall these images need to be seen in their large format state.

In Heads, an adolescent boy in a baseball cap is, as DiCorcia put it, “pure Holden Caulfield”. Next to him, a young girl is freeze-framed with “a perfect Botticelli wind blowing through her hair”. Both seem unreal in the way that many of DiCorcia’s portraits are: they emerge out of the darkness with other ghostly faces around them, each lost in their own reverie. Though the context is set up, the results capture the intimate naturalism of faces picked out in the hustle and bustle of New York streets, but the clamour of Times Square is silenced by the darkness that lies just beyond this cinematic lighting.

There’s a deeper melancholy about Hustlers that is not just to do with the desperate nature of street prostitution, but more with the way the subjects pose – often looking off into the distance – and the way their loneliness is accentuated by the dreamy light and neon romance of Los Angeles. DiCorcia, shooting on film and printing on high-end inkjet, and his colours often have an oddly nostalgic feel that recalls the soft gleam of Kodachrome. Whereas the light falling on a yellow rainhat in one of the Heads portraits makes the fabric seem even shinier, the light on the rent boys is softer, making them seem like Hollywood hopefuls on the hustle for a starring role – the very reason some of them gravitated to Los Angeles in the first place.

A Storybook Life. are small photographs are personal and often diaristic: they show the ebb and flow of ordinary life – even though many are posed or semi-staged – and, in their non-chronological waywardness, accentuate it.

Research

Websites accessed 17/11/19

https://www.nytimes.com/2001/09/14/arts/art-in-review-philip-lorca-dicorcia-heads.html

https://americansuburbx.com/2011/09/interview-photographer-philip-lorca-dicorcia-talks-2003.html

Andreas Gursky (b.1955)

Emerging from the Düsseldorf School in the late 1980s, Andreas Gursky was pivotal in creating a new standard in contemporary photography, a pioneer who furthered the possibilities of scale and ambition. His massive, clinical, and distanced surveys of public spaces, landscapes, and structures contributed to a new art of picture taking in contrast to the Minimalism and Conceptualism of the 1970s. His use of large-format cameras, scanning, digital manipulation, the layering of multiple pictures to create a cohesive image, and technical postproduction positioned him as an important bridge between the old ways of shooting and presenting pictures and the current highly, technologically advanced era of photography.

Vast, large places are of particular interest to Gursky such as stock exchanges, concert arenas, big box stores, sweeping landscapes, racetracks, and other locations, which engage in regular relationship with the human population. His monumental photographs of these environments have the effect of fully encompassing the viewer within the spaces they aim to portray.

Gursky’s photographs are often shot from an elevated, aerial perspective. This allows viewers to experience a scene in its full proportions, which would ordinarily be impossible, allowing for a visual comprehension of scope, center, and periphery.

A straightforward and distanced observation informs Gursky’s work, leaving the viewer to formulate their own opinions and responses.

Aggregate space performs largely in the success of each work. Even though his subject matter exists prior to his encounter with it, he manages to masterfully reveal its inherently harmonious sum of individual parts where objects become elements such as strata, line, geometry, colour, and form.

Gursky’s photographs create a dialogue between painting and representation in that they go beyond merely capturing a piece of visual documentation – they in fact oftentimes conjure the look and feel borrowed from such movements as Abstract Expressionism and Minimalism.

Although Gursky refrains from social or political commentary with his work, he admits an overriding interest in capturing the existence of globalism and consumerism as it relates to modern man.

Research

Websites accessed 17/11/19

http://www.bbc.com/culture/story/20151106-andreas-gursky-the-bigger-the-better

http://www.eyemagazine.com/opinion/article/fabricated-reality

Luc Delahaye (b.1962)

Amidst the crowd of photojournalists reporting on global current affairs, Luc Delahaye plays two parts: his panoramic views show both the significant and banal details of a historic event, while deliberately suspending the function of the journalistic image. Drifting away from conventional media narratives, his photographs do not intend to provide visual proof of a current event; they seem to search instead for an estranged perspective on the line of fire. The range of his reportage – a riot in Gaza, the aftermath of the 2010 Haiti earthquake, the life of the lumpenproletariat in France or the United Arab Emirates – addresses the problematic practice of photojournalism itself.

Operating as a professional war reporter between the late 1980s and the early 2000s, Delahaye earned international recognition for his work in war zones. But from 2001, the year of his first gallery show, and especially 2004 when he left the Magnum Photos agency, his work underwent a critical turn: panoramas replaced close-ups and editorial commissions were abandoned for grand museum-scale tableaux. Delahaye’s migration from journalism to ‘art photography’ as a result of a crisis of belief in journalistic truth became a framework in itself and the keystone for a reborn practice, where the constraints of information were suspended in favour of an interrogative perception of facts.

Research

Websites accessed 17/11/19

https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2011/aug/09/luc-delahaye-war-photography-art

https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2004/jan/31/photography

https://newrepublic.com/article/124034/war-photography-beautiful-damned

Hannah Starkey (b.1971)

A British photographer who specialises in staged settings of women in city environments. She uses actors within considered settings that are reconstructed from everyday life but very much in a stylised film format. The women seem to be mainly engaged in regular routine activities such as sitting in cafes or shopping, however they all seem to be detached, cold and emotionless.

It is said that she uses composition to heighten the sense of personal and emotional disconnection, with arrangements of lone figures separated from a group, or segregated with a metaphoric physical divide such as tables or mirrors.

When I first started out, photography was very male and not really considered art,” says Hannah Starkey. “I didn’t set out to have a feminist agenda, it was more that my interest in making work about women comes from the simple fact that I am one. That commonality of experience is at the heart of what I do as an artist.”

“In the beginning, I wanted to create a hybrid out of the different approaches I had been taught,” she says, “by somehow bringing together the emotive language of documentary with the slickness of advertising and the observational style of street photography. I think I’ve become more reflective and considered, but the performative element has been a constant.”

Her MA show featured seven large-format photographs of young women interacting, their style and compositional skill self-consciously referencing both classical painting and elaborate film stills. It caught the attention of London gallerist Maureen Paley, who left a note for her at the college and has represented her ever since.

“That graduate show set me up,” says Starkey. “Suddenly I was in demand and simultaneously I became very aware of the different space that women occupy in the photography world, both as practitioners and subjects. I have been acutely aware of that ever since, the ways in which women are constantly evaluated and judged. My gaze is not directed in that way. A lot of what I do is about creating a different level of engagement with women, a different space for them without that judgment or scrutiny.”

Research

Websites accessed 18/11/19

https://www.itsnicethat.com/articles/hannah-starkey-mack-books-publication-photography-040119

https://loeildelaphotographie.com/en/hannah-starkey-photographs-1997-2017-bb/

https://www.telegraph.co.uk/culture/photography/8283609/Hannah-Starkey-In-Conversation.html

Julia Fullerton-Batten (b. 1970)

Julia is a world-wide acclaimed and exhibited fine-art photographer with the foundation of her success being the series ‘Teenage Stories’ (2005), an evocative narrative of the transition of a teenage girl to womanhood. It portrays the different stages and life situations experienced by an adolescent girl as she grapples with the vulnerability of her teenage predicament – adjustments to a new body, her emotional development and changes in her social standing. Her book ‘Teenage Stories’ was published in 2007. This success was followed by other projects illuminating further stages a teenager experiences to becoming a woman – In Between (2009) and Awkward (2011). Julia freely admits to many of her scenes being autobiographical. This was even more so the case with her next project, Mothers and Daughters (2012). Here she based the project on her own experiences in her relationship with her mother, and the effects of her parents’ divorce. Unrequited love – A Testament to Love (2013) – completes Julia’s involvement with the female psyche, illustrating poignantly the struggles experienced by a woman when love goes wrong. Again, there is no happy end, the woman is left with the despair of loneliness, loss and resignation.

More recently, Julia has shot a series of projects where she has engaged with social issues. Unadorned (2012) takes on the issue of the modern Western society’s over-emphasis on the perfect figure, both female and male. For this project she sourced overweight models and asked them to pose in the nude in front of her camera against a backdrop similar to that of an Old Master’s painting, when voluptuousness was more accepted than it is now. ‘Blind (2013)’ confronts the viewer with a series of sympathetic images and interviews with blind people, some blind from birth, others following illness or an accident. Sight being one of mankind’s essential senses and her career being absolutely dependent on it, Julia hoped to find answers to her own personal situation if she were ever to become blind. In Service (2014), exposes some of the goings-on behind the walls of the homes of the wealthy during the Edwardian era in the UK (1901 – 1911). Millions of poorer members of society escaped poverty by becoming servants in these homes, where it was not only hard work, but they were often subjected to exploitation and abuse.

‘Feral Children’, (2015), Julia re-enacts fifteen reported cases of feral children with child actors. The cases involve a variety of different circumstances in which children were rejected or abused by their parents, others got lost or left in the wild, and some were captured by wild animals.

Julia’s use of unusual locations, highly creative settings, street-cast models, accented with cinematic lighting are hallmarks of her very distinctive style of photography. She insinuates visual tensions in her fine-art images, and imbues them with a hint of mystery, which combine to tease the viewer to re-examine the picture, each time seeing more content and finding a deeper meaning. These distinctive qualities have established enthusiasts for her work worldwide and at all ends of the cultural spectrum, from casual viewers to connoisseurs of fine-art photography.

Research

Websites accessed 18/11/19

https://www.dodho.com/the-act-julia-fullerton-batten/

https://www.dodho.com/interview-with-julia-fullerton-batten/

https://www.itsnicethat.com/articles/julia-fullerton-batten-2

https://thechiswickcalendar.co.uk/fine-art-photographer-julia-fullerton-batten-profile/

https://www.mastersof.photography/julia-fullerton/

Tom Hunter (b. 1965)

Hunter prefers to work slowly using a Wista 4 x 5 camera and also a large format pinhole camera. After leaving school with only one qualification he seemed to work his way through a number of jobs before undertaking a night class in photography.

“People have got a bit too excited about digital technology, thinking you’ve got to have the latest digital this, that and the other,” he tells me. “But it’s not about the equipment, it’s about capturing the light – you can take pictures on anything. You don’t need to spend £1500 on the latest digital multitasking thing. Going to a church hall and taking maybe three pictures in an hour is going back to basics. It’s like slow cooking. I like that methodical way of working, not walking around taking lots and lots of shots.”1

He graduated in 1994 from London College of Printing with a first class honours degree and began by photographing his friends and neighbours living in squats , but rather than depicting the squat dwellers as misfits and victims he wanted them to be perceived in a more dignified way. For me his images are taken with consideration of both the light and composition.

“I had got very sick of seeing people I knew, travellers and squatters, presented in the media in black-and-white images with captions saying, ‘These people are scum’. I was saying, ‘We’re not scum, we’re just people like anyone else and we need to be shown’. Even though I lived in a squat, I never thought I was outside of society. I always felt I was part of this country and that my voice should be heard. I thought by using colour and by using certain ways of depicting people I could create more empathy.” 1

He also comments “colour and light became key to the way I looked at my neighbourhood”2 He has continued to use friends and the inhabitants of his Hackney community to convey local issues which include elements of realism believing that “images are real yet created by the person manipulating the camera” 2

Hunter states that his inspiration is drawn from the artist Johannes Vermeer. The images are produced to highlight the seriousness of the situations he and his neighbours found themselves in – most will not understand and only see the beauty in the image.

“Newspaper headlines come and go. I want to show that they are very serious and that what goes on around you is very important,” he says. “I wanted to make them monumental, and put them in The National Gallery. There is an argument that aesthetics creates a barrier; I’m arguing it takes the barrier down and helps you engage more“.1

Hunter research and discovered that there was limited information about Vermeer, but he is believed by some to have used a camera obscura and it is this relationship with photography in Vermeer’s paintings that fascinated Hunter. Vermeer’s paintings of his small local community are intimate with minutiae details , Hunter calls him a “painter of the people” 2, and describes Vermeer’s work as “magical and amazing” 2 For me reviewing Hunter’s work that same approach can be seen in the projects he has undertaken in his local community highlighting the beauty that exists in the most unlikely of places.

Hunter acknowledges that there is a downside in his creations and limiting the audience to small exclusive galleries, when he really wants to reach out to the world:

“But there are downsides to everything, and the downside of the art world can be that suddenly you’re producing a commodity, and your work is being bought by rich people and shown quite exclusively to them. For me, it’s been really important to go beyond just a small West End gallery where I will only communicate with a few people. I didn’t want to become ghettoised in the art world – if I was just trying to create beautiful objects that would be fine, but I’m trying to put across a message as well.” 1

Hunter’s image of the woman reading a possession order captures a private and personal moment with integrity and is proof that art can force change. It also highlights the influence Vermeer has over his work. Due to the influence the image had the re-possession never took place , Hunter creates “art with a social impact” 2 .

I also found the following YouTube interesting (accessed 23/02/19):

Research

Access 20/11/19

1 http://www.tomhunter.org/think-global-act-local/

2 http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b00zt7ky

Personal Journeys and Fictional Autobiography

Nan Goldin (b. 1953)

Nan Goldin is an American photographer known for her deeply personal and candid portraiture. Goldin’s intimate images act as a visual autobiography documenting herself and those closest to her, especially in the LGBTQ community and the heroin-addicted subculture. Her opus The Ballad of Sexual Dependency (1980–1986) is a 40-minute slideshow of 700 photographs set to music that chronicled her life in New York during the 1980s. The Ballad was first exhibited at the 1985 Whitney Biennial, and was made into a photobook the following year. “For me it is not a detachment to take a picture. It’s a way of touching somebody—it’s a caress,” she said of the medium. “I think that you can actually give people access to their own soul.” Born Nancy Goldin on September 12, 1953 in Washington, D.C., the artist began taking photographs as a teenager to cherish her relationships with those she photographed, as well as a political tool to inform the public of issues that were important to her. Influenced both by the fashion photography of Helmut Newton and Guy Bourdin she saw in magazines, as well as the revelatory portraits of Diane Arbus and August Sander, Goldin captured herself and her friends at their most vulnerable moments, as seen in her seminal photobook Nan Goldin: I’ll Be Your Mirror (1996). In 2018, she collaborated with the clothing brand Supreme by including three of her photographs, Misty and Jimmy Paulette in a taxi, NYC (1991), Kim in Rhinestones, Paris (1991), and Nan as a dominatrix, Cambridge, MA (1978) on their spring/summer collection.

Nan Goldin photographs her life, her friendships and loves, her losses and addictions, good times and bad times. Little, if anything, is off-limits. Goldin’s images stand in for memories, with its lapses, repetitions, the mess we leave behind, all mingled with the people who are gone, and the things we cling to. ‘Memory Lost’ reworks it all, running past and present into something like a narrative. As unwieldy and sprawling as it is, her work attempts to grapple with it. All her work, I think, is a kind of memoir, an insistent retelling of the same things over and again in different ways .

Research

Access 20/11/19

https://www.theartstory.org/artist/goldin-nan/

https://www.guggenheim.org/artwork/artist/nan-goldin

Larry Sultan (1946 – 2009)

Larry Sultan was an American photographer known for his use of images to create a discourse between fiction and documentary. The seminal photobook Pictures ‘From Home’ (1992), achieved this difficult ambiguity through combining film stills from home movies, contemporary photographs of suburbia, and texts from his journal. “What drives me to continue this work is difficult to name. It has more to do with love than with sociology. With being a subject in the drama rather than a witness,”

Sultan, a prominent fine art photographer who repeatedly reached back to the San Fernando Valley of his youth to lyrically explore the dark side of the suburbs and the American dream. “He has been such an influential figure, not only regionally but internationally,” said Britt Salvesen, curator of photography at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. “He was a really intelligent exporter of ideas about California and about photography . . . a significant thinker as well as an image maker,” she said.

He considered himself a “photographic scavenger” and his first major project, in 1977, reflected that. With Mike Mandel, a photographer he’d met in art school, Sultan spent two years combing through images to assemble “Evidence,” an exhibit of photos originally made as records for industry, police or government.

Stripped of identifying information, the photos were taken out of context and became “mysterious, humorous, ominous and, often, beautiful,” art critic William Wilson wrote in The Times when they were displayed in 1977 at the Los Angeles Institute of Contemporary Art.

For another major project, “Pictures From Home,” Sultan spent 10 years putting together a portfolio that mixed images from his family’s snapshot and movie archives with formal photographs of his parents, shown in retirement in Los Angeles and Palm Desert.

The work was “about family history and the American dream, and how those two intersect,” Sultan told The Times in 1989. “My father bought a one-way ticket from New York in 1949 and ended up in a dream house in Sherman Oaks. It was part of the cultural myth of the ‘50s about going west.”

“Pictures From Home” grew out of Sultan’s notion that a family’s story can have as many versions as there are family members. He also was intrigued by his father’s forced early retirement. Sultan had his parents act out ordinary moments, such as cooking dinner or practicing a golf swing. The results could seem stilted but also yielded unexpected spontaneity, critics said. In 1989 they were shown at New York’s Museum of Modern Art.

Research

Access 20/11/19

http://www.artnet.com/artists/larry-sultan/

https://time.com/3562317/the-influence-and-legacy-of-larry-sultan/

https://www.sfchronicle.com/art/article/Larry-Sultan-exhibit-showcases-photographer-s-11052899.php

https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2009/dec/17/larry-sultan-obituary

Richard Billingham (b. 1970)

Ray’s a Laugh’ can be considered a number of things; a social documentary of alcoholism; poverty; mental abuse. For me it’s a collection of exposed, intimate snapshots of family life that isn’t all its made out to be. Richard Billingham, has expressed how this depiction of his family happened by chance – his original purpose for capturing them was as aids to paintings he had hoped to create. The narrative of life in this council flat in the Midlands (which can be seen in the video link above) unintentionally has become one of his most recognised pieces of work and casts Ray and Elizabeth as celebrities in their own right. ‘Ray’s a Laugh’ was published as a photo book in 2000.

Expectation versus reality comes into play in Billingham’s images leaving a ‘sickly unease in the eye of the onlooker’. The expectation is one of comfort, the domestic setting mundane and ordinary with the form used furthering the fluency of the everyday within the photographs, Billingham himself noting how he ‘just used the cheapest film and took them to be processed at the cheapest place,’. These images not only deconstruct the stereotypical family portrait but fundamentally challenge the accepted presentation of suburban life, exposing the façade of happy families and revealing a dark truth. Unusual in every sense this series ‘depicts the reality of a dysfunctional family and their domestic environment, each photograph laced with issues of alcoholism, violence and unemployment’.

Therefore, this likens Billingham to social photographers who document the conditions of human life in order to reveal the need for reform and progression such as Lewis W. Hine. Recording ‘social injustice’ amongst the working class stands forefront within the work of Hine, however, the real link with Billingham is their shared desire to show ‘individual human beings surviving with dignity in intolerable conditions.’ Whilst Hine conveys the triumph of steel workers in their comradery sat side by side eating lunch, the survivor within ‘Ray’s a laugh’ is Billingham himself. There is an awareness of the distance and separation of the photographer in even the most intimate of photographs such as Ray lying in bed asleep or clinging to the toilet post alcoholic-purge. This domestic photography results in Billingham’s presentation of himself as an outsider looking in. Sometimes invasive and sometimes comical, his series combines elements of social and domestic photography in order to depict humanity in its rawest form, and he does it so brilliantly.

Vibrancy of colour is perhaps one of the most striking fundamentals of these photographs, the vivid contrast highlighting the detail of Liz’s tattoos and Ray’s tobacco stained fingers and impressing a ‘realness’ in the moments that the unconventional love of the two is depicted. The injection of life that colour gives to these photos emphasises the chaos and clutter of their family home, overcrowded with painted porcelain ornaments and trinkets, peas and carrots dropped on the kitchen floor starkly green and orange against the muddy white of the tiles. It is these seemingly insignificant details that engage the observer.

![Richard_Billingham_Rays_a_laugh_p07[1]](https://michele512879level3.photo.blog/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/richard_billingham_rays_a_laugh_p071.jpg?w=564&h=361)

![20101025010655_richard_billingham_untitled12[1]](https://michele512879level3.photo.blog/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/20101025010655_richard_billingham_untitled121.jpg?w=511&h=344)

Research

Access 20/11/19

https://www.saatchigallery.com/artists/richard_billingham.htm

http://www.anothermag.com/art-photography/1124/richard-billingham

Responding to the Archive

Alan Sekula’s ‘Reading an Archive: Photography between Labour and Capital’ in Evans, J. & Hall, S. (eds.) (1999) Visual Culture: The Reader, London: Sage

The essay, which I found in places hard to follow, begins by highlighting the importance of understanding the circumstances under which the image was created at the time. Sekula emphasises that the viewer of the photograph should consider the relationship between subject and photographer and the historical approach and attitude towards the use of photography at the time – i.e. was it purely for record purposes or was there a more human aspect for the recording of the event?

Photographic meaning is dependent on context and so meaning is flexible often depending on where the images are taken, used and what if any text may be used to help the viewer understand the meaning behind them. Conventionally photographs were felt to depict the truth but as we have seen in other aspects of the course to date this is not necessarily true, the truth too depends on context, processing and the photographers bias.

It is often considered interpreted that photographs taken from an archive are historical documents and considered to be a true representation of the truth but Sekula discusses the need to be aware that with the dependence of mass culture and education leaning heavily on photographic realism the reader is apt to mistake historical interpretation for historical fact and historical photographs can give the appearance of showing history itself case in point would be the work by Alexander Gardner who moved the body of a solder to ‘document’ the battleground. Thus, photographic truth is confirmed by accompanying text and the text has its own form of truth which may or may not be confirmed by the photograph. From this method of using photography we find historical and social memory manipulated, changed and rewritten. We all know how our own memory changes with time, events and age. The wide spread use of photography to illustrate history gives the impression that certain events pictured are more significant than others and so gives preference to a particular version of history. It will be interesting to see how in the years to come the images produced today truly reflect the events and how many remain archived.

As an alternative Sekula asks us to consider the images found within an archive as ‘works of art’. Using this approach, the photographer would be elevated to the position of an author. Sekula draws our attention to the use of the myth which he calls the “neo-romantic auterism” and details “the problem with auterism, as with so much else in photographic discourse, lies in its frequent misunderstanding of actual photographic practice. In the wish fulfilling isolation of the ‘author’ one loses sight of the social institutions – corporations, school, family –that are speaking by means of the craft work of the commercial photographer’s craft”. This implies a collaboration at the heart of commercial practice.

To conclude Sekula suggests we approach an archive as a ‘complex repository of images’ that can have many different interpretations. When using we must be critically aware of how society has approached photographs. We also need to be aware of the historical claims made and how it has been an objective, and scientific way of seeing the world whilst also being a subjective means of self-expression.

Taryn Simon (b. 1975)

Archives exist because there’s something that can’t necessarily be articulated. Something is said in the gaps between all the information.

—Taryn Simon

Taryn Simon directs our attention to familiar systems of organisation—bloodlines, criminal investigations, flower arrangements—making visible the contours of power and authority hidden within. Incorporating mediums ranging from photography and sculpture to text, sound, and performance, each of her projects is shaped by years of rigorous research and planning.

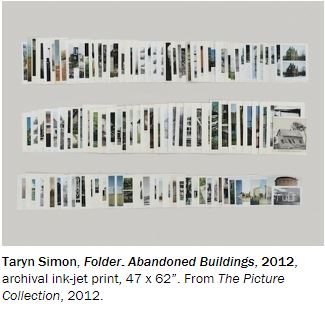

In 2012–13 Simon began work on Image Atlas (2012–) and The Picture Collection (2013–), projects that bridge physical and digital archives. The former, created with computer programmer Aaron Swartz, investigates cultural differences and similarities by indexing top image results for given search terms across local search engines throughout the world. The latter was inspired by the New York Public Library’s picture archive, whose 1.2 million printed images, organized under more than 12,000 subject headings, comprise the largest circulating picture library in the world.

This body of work delves deeper into a theme that preoccupies much of Simon’s work, that of examining how the photographic image is classified and catalogued. Simon is fascinated with how this system presages image search engines like Google Image, but also how much chance and accident, arbitrary inclusion and exclusion, is written into the system.

Simon’s practice can best be described by the words of Simon Baker, first curator of Photography at the TATE Modern: “There are a small number of photographers who combine the visual and the textual so powerfully, and whose work is sophisticated in terms of contemporary art practice but also hard-wired to the real world. Taryn Simon is certainly one of them.”

I first came across Taryn Simon in the Context and Narrative course Assignment five where I highlighted that the invention of digital photography and the ever-increasing power of editing software has made it easy for anyone to alter images. People no longer have the same faith in photographs as a form of truth (excluding those from crime scene), the airbrushing of fashion models being a case in point, even with glass plate or negative film there has been a degree of manipulation of the image in the darkroom causing question as to the truth behind the image a good example would be the ‘Cottingley Fairies’ (1917), were the truth was not revealed until 1970. There is an ever-increasing blurring of the boundaries between truth and fiction. This has in a number of cases resulted in mistakes by eye witnesses that have relied on photographic evidence or memory. This was highlighted by Taryn Simon in her photographic project ‘The Innocents’. The work consists of portraits of people who were wrongly convicted of a crime based on eye witness testimony ‘the question of photography’s function as a credible eyewitness and arbiter of Justice’

Photographs can and do play tricks on the mind. As Simon demonstrates in her TED talk from 2009, the camera:

‘confronts constricted realities, myths and beliefs and appears to be evidence of a truth. But there are multiple truths attached to every image depending on the creator’s intention, the viewer and the contact in which it is presented’

Research

Access 20/11/19

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Taryn_Simon

https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2011/may/22/taryn-simon-tate-modern-interview

Simon, Taryn (2003): Artist statement for the innocents. [website]: URL:http://tarynsimon.com/works_innocents.php;

Simon, Taryn (2009): Photographs Secret Sites. [On-Line]: TED Global video: URL:http://www.ted.com/talks/taryn_simon_photographs_secret_sites.html;

Nicky Bird

Dr. Nicky Bird is a PhD Coordinator at the Glasgow School of Art (1) but also a practicing artist whose work involves the combination of new and found photographs (2) in order to support the exploration of social and hidden history. Her project ‘Tracing Echoes’ dated 2001 when she was the artist in residence at Dimbola Lodge, the home of Julia Margaret Cameron.

In 2006 through to 2007 she created ‘Question for Seller’ where she purchased unwanted family photos on ebay and exhibited them with the sellers comments and their original purchase price. At the end of the exhibition the photos were resold. This project raised a series of questions about the value placed on a family’s history and how a family album moves from being a cherished possession to a commodity.

In the interview with Sharon Boothroyd (3) Bird touches on how this process might be connected with class and the way in which working class history only exists at the margins.

Research

Access 29/11/19

1 http://www.gsa.ac.uk/research/cross-gsa-profiles/b/bird-nicky/

2 https://nickybird.com/about/

3 https://photoparley.wordpress.com/category/nicky-bird/

http://seesawmagazine.com/sellerpages/sellerintro.html

https://nickybird.com/projects/question-for-seller/

Psychogeography

The term psychogeography was invented by the Marxist theorist Guy Debord in 1955. Inspired by the French nineteenth century poet and writer Charles Baudelaire’s concept of the flâneur – an urban wanderer – Debord suggested playful and inventive ways of navigating the urban environment in order to examine its architecture and spaces.

As a founding member of the avant-garde movement Situationist International, an international movement of artists, writers and poets who aimed to break down the barriers between culture and everyday life, Debord wanted a revolutionary approach to architecture that was less functional and more open to exploration.

Psychogeography gained popularity in the 1990s when artists, writers and filmmakers such as Iain Sinclair and Patrick Keiller began using the idea to create works based on exploring locations by walking.

http://www.thedoublenegative.co.uk/2014/12/an-introduction-to-psychogeography/

In terms of psychogeography, do you think it’s possible to produce an objective depiction of a place or will the outcome always be influenced by the artist? Does this even matter?

When photography was introduced over 150 years ago it was often considered to be the perfect solution to document moments and world history in an objective and unbiased manner. Since then technology has advanced and there is no longer the need for individuals to sit still for the long exposures previously required, the camera has become portable, light and available to the masses. In the area of photo journalism the people were able to see clearer and more realistic images. Images have come to play a central role in communication. The use of images in politics, news media, magazines, internet, social media has resulted in photography becoming a prime form of communication and influence in the development of our world (see Sontag, 1973; Barthes, 1975 and 1980). “for the first time the public saw photographs of bored ministers, ungainly postures, and cunning smiles behind cigar-smoking officials.” This according to historian Judith Gutman (1990). Photography was exposing the warts and all images and so the general public decided that what they saw was credible – a picture never lies!

Our perception of the photograph as inherently realistic is also inseparably bound to our faith in technology. Many photographers will claim their images represent the undistorted truth when in fact there are a large number of manipulations been film/senor and publication – these maybe as simple as removing dust spots or as major as a crop to remove objects or individuals.

Other types of manipulation take place during the actual act of taking the image. The photographer, by actually taking the image selects the subject matter, the composition includes or excludes items and therefore will change the mood and impact of the image. He/she is manipulating the result before it is even taken. According to Geoffrey Batchen (1994), Art critic:

‘[T]raditional photographs – the ones our culture has always put so much trust in – have never been “true” in the first place. Photographers intervene in every photograph they make, whether by orchestrating or directly interfering in the scene being imaged; by selecting, cropping, excluding, and in other ways making pictorial choices as they take the photograph; by enhancing, suppressing, and cropping the finished print in the darkroom; and, finally, by adding captions and other contextual elements to their image to anchor some potential meanings and discourage others’

Although the above statement was made about film, computer technology and the advancement of cameras, sensors and lenses has created a whole new realm of ethical uncertainties. The use of this technology means that images can be altered seamlessly. To put it simply – the use of this technology has forced everyone to acknowledge that the image has been manipulated and the image is never will represent the “truth”. Batchen says:

‘Digitization abandons even the rhetoric of truth that has been an important part of photography’s cultural success….newspapers have of course always manipulated their images in one way or another. The much-heralded advent of digital imaging simply means having to admit it to oneself and even, perhaps, to one’s customers.’

As technology gets cheaper and systems become more powerful there are so many ways to manipulate digital images. With this accessibility there is the ever growing debate around the acceptable levels of manipulation – the airbrushing of social/media celebrities to the to the deliberate removal of people or items that may have a major political affect means we are reliant on the integrity of the communicator – in this case the photographer and the editor but as consumers of this form of communication it should be taken with a healthy dose of scepticism.

Research

Barthes. Roland. Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography. Tr. Richard Howard. New York: Hill, 1981.

Barthes. Roland. “The Photographic Message.” The Responsibility of Forms: Critical Essays on Music. Art. and Representation. Tr. Richard Howard. New York: Hill, 1985, pp. 3-20.

Geoffrey Batchen, “Phantasm: Digital Imaging and the Death of Photography,” Aperture 136 (1994): 48.

Judith Mara Gutman, “The Twin-Fired Engine: Photography’s First 150 Years,” Gannett Center Journal 4 (1990): 58

Sontag. Susan. On Photography. New York: Farrar. Straus and Giroux, 1973

Pedro Guimaraes

I have to admit I couldn’t really find much on Guimaraes but “‘Bluetown’ is, according to Guimarães, ‘a dream of London about itself, a celebration of the beauty of its own alienation and loneliness’. To find ‘Bluetown’, Guimarães superimposed an outline of Queen Elizabeth’s face on the map of London on which he plotted evenly spaced points, a grid of geographic coordinates. Following the route set by this symbol of ‘Englishness’, he then visited and photographed each location.”

Research

Access 07/12/19

http://pedroguimaraes.net/studio/index.php?/albums/bluetown-1/

Francis Alys (b. 1959)

Alÿs, born in Belgium but has lived in Mexico City since 1986. On reviewing his work it is clearly based on his confrontation with South America’s promise to modernise but to then result in delays.

The work Paradox of Praxis I (1997) (also titled Sometimes Doing Something Leads to Nothing), shows Alÿs pushing a large block of ice around Mexico City’s centre. This is an attempt of the outsider, steadily trying to grapple with his environment, only to see his hopes and dreams failing.

When Faith Moves Mountains (2002) is Alÿs’ largest project. 500 Peruvian students, each with shovel in hand, were asked to walk in a line up a sand dune on the outskirts of Lima. Their systematic shovelling and scooping ensured that this mountain did indeed move a few centimetres. Alÿs attempt at highlighting the lack of action in the Latin American modernisation schemes.

The Green Line is a work stemming from an action Alÿs carried out in São Paulo in 1995, where he dribbled blue paint from an open paint can as he walked from the gallery, around the city and back to the gallery again.

The armistice border in Jerusalem, known as ‘the green line’, was mapped out with a pencil at the end of the war between Israel and Jordan in 1948. This remained the border until the Six Day War in 1967, after which Israel occupied the Palestinian-inhabited territories east of the line. Alÿs, with his walk, maps this very border whilst dribbling green paint behind him from an open tin. His reflection that ‘sometimes doing something poetic can become political and sometimes doing something political can become poetic’ is really the core of this piece of work.

Research

Access 07/12/19

https://www.nytimes.com/2011/05/06/arts/design/francis-alys-a-story-of-deception-at-moma-review.html

https://www.aestheticamagazine.com/review-francis-alys-tale-negotiation-tamayo-museum-mexico-city/

https://www.artnews.com/art-in-america/aia-reviews/francis-alys-60968/

https://artreview.com/features/summer_2016_feature_francis_alys/

https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2010/jun/20/francis-alys-ernesto-neto-review

Stephen Gill (b. 1971)

Stephen Gill’s practice seems to be driven by a desire to connect with his immediate surroundings – be that the wildlife that surrounds his home in Sweden, to the years he spent cycling through Hackney Wick. It goes back to his childhood, “My hobby morphed into what I do for a living,” he reflects. “Making this new work took me right back to those early years, as if completing a full circle.”

‘The Pillar’ is a 20 self-published photobook and follows on from Gill’s prior work ‘Night Procession’, when he used a lo-fi motion sensor camera to photograph wild animals as they roamed the night. In a similarly manner ‘The Pillar’ uses a camera in a nearby farm, opposite a pillar of wood. “It was like magic!” he says. From a tree sparrow to a golden eagle. The Pillar is Gill’s second book since moving to Sweden in 2014. After living in London for 20 years, he felt it was time to slow down. “In London you are so visually bombarded,” says Gill. “It was great for my work, but I never rested in 20-odd years.” But he adds that he soon found out that wasn’t London that was over-stimulating him, “It was me,” he says. “I’m still doing the same since moving here… I just love making things. It’s not anything to do with ambition, when I make things I feel really relaxed.”

The region of Skåne, where he lives, is home to 192 species of the 250 birds that are native to Sweden. Gill managed to attract 24 species to his pillar – as well as a fox. “In a way, the birds made the work themselves, I’ve just orchestrated an environment in which the pictures can be born,” says Gill, who finds that nature is too often presented in absolute clarity, “like a wildlife show”. “That clarity can suffocate nature, it can suffocate the spirit of the animals. I love how [the birds in The Pillar] are not fully settled. The lack of clarity gives them a little more breathing space.”

Many of Gill’s projects have an obsessive quality to them, often expressed through collecting and reusing found objects. For ‘A Series of Disappointments’ (2008) Gill scoured the doorsteps of bookmakers, gathering 71 failed betting slips – each screwed up into tiny sculptures of frustration – which he photographed and presented in a book. Similarly, in ‘Off Ground’ (2011), he collected bits of rubble from the aftermath of the Hackney riots, and for ‘Talking to Ants’ (2014), he attached found objects from the local area to his camera lens, creating what he calls an “in-camera photogram”. Other projects see him experimenting with the process of making images, such as ‘Hackney Wick’ (2004), which he shot on a plastic camera bought in the market for 50p.

Research

Access 07/12/19

https://www.theguardian.com/books/2019/may/28/the-pillar-stephen-gill-review

https://theodreview.com/2019/06/06/the-pillar-stephen-gill-reviewed-by-robert-dunn/

http://theheavycollective.com/2019/08/26/review-stephen-gill-the-pillar-nobody-books/

https://www.lensculture.com/stephen-gill

https://www.stephengill.co.uk/portfolio/news

https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2004/may/15/photography

Conceptual Photography

According to Wikipedia: Conceptual photography is a type of photography that illustrates an idea. The ‘concept’ is both preconceived and understandable in the completed image. It is most often seen in advertising and illustrations where the picture may reiterate a headline or catchphrase that accompanies it. Photographic advertising and illustration commonly derive from Stock photography, which is often produced in response to current trends in image usage as determined by the research of picture agencies like Getty Images. Conceptual art of the late 1960s and early 1970s often involved photography to document performances, ephemeral sculpture or actions. The artists did not describe themselves as photographers, for example Edward Ruscha said “Photography’s just a playground for me. I’m not a photographer at all.” These artists are sometimes referred to as conceptual photographers but those who used photography extensively such as John Hilliard and John Baldessari and Pedram Mousavi are more often described as photoconceptualists or “artists using photography”

Research

Access 07/12/19

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Conceptual_photography

https://www.tate.org.uk/art/art-terms/c/conceptual-photography

http://truecenterpublishing.com/photopsy/conceptual.htm

Source photographic journal made three films asking photographers, artists, curators and editors for their response to the question ‘What is conceptual photography?’ No-one had any clear-cut answers but there are some interesting opinions being discussed, like alternative views to straight photojournalism by Adam Broomberg and Oliver Chanarin. John Hilliard talks about being known as a conceptual artist in the 1960s and 70s. Hilliard is still taking photographs today.

Watch the video and then write a paragraph explaining what you understand by the term ‘conceptual photography’. Provide some examples of recent work that you believe falls into this category.

www.source.ie/feature/what_is_conceptual.html [Access 07/12/19]

For me Conceptual photography is all about speaking through the photograph. Each image should once captured be capable of portraying a very powerful message, however abstract the concept maybe. It seems that this form of photography has gained importance since its conception in the 1960s. Conceptual art brings a new meaning to photography. Rather than the usual two-dimensional image, conceptual photographs use creativity to evoke abstract ideas and emotions.

One of the main features of conceptual photography is the fact that artists design the scenes and prepare them meticulously to accentuate their messages. This sometimes involves including impossible or exaggerated components or manipulating the piece with digital editing for high impact.

Some of the photographers I came across during my review of this genre are:

Chema Madoz (b. 1958): This Spanish artist is considered an international leader in conceptual photography. He has been awarded the National Photography Prize and the Higashikawa Award, among others, and has shown in galleries and museums the world over.

http://www.spainisculture.com/en/artistas_creadores/chema_madoz.html [accessed 07/12/19]

Jordi Larroch (b. 1978): is a spanish photographer and poet whose work combines slightly altered everyday objects to give them a new meaning. Larroch’s photographs are divided into two series (Black and White).

http://jordilarroch.com/ [accessed 07/12/19]

Amy Stein (b. 1970): Amy Stein is an American photographer. Some of her photo series include Stranded and Domesticated. Stein’s work explores our relationship with the wild and the impact of our impulses on human and animal behaviour.

https://amysteinphotography.zenfolio.com/

David Levinthal (b. 1949): An American photographer famed for using dolls and toys in dramatically lit scenes that give them a human appearance. Most of his work refers to American pop culture and colour TV.

http://davidlevinthal.com/ [accessed 07/12/19]

Heidi Lender: this American photographer started out writing about her experiences in photo sessions for fashion magazines. Behind the camera, Lender explores the condition of humanity. Self-portraiture is a frequent theme in her work.

![tom-hunter-the-way-home-(from-life-and-death-in-hackney)[1] tom-hunter-the-way-home-(from-life-and-death-in-hackney)[1]](https://i0.wp.com/michele512879level3.photo.blog/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/tom-hunter-the-way-home-from-life-and-death-in-hackney1.jpg?w=370&h=296&ssl=1)