Modernist Photography

A general term used to encompass trends in photography from roughly 1910-1950 when photographers began to produce works with a sharp focus and an emphasis on formal qualities, exploiting, rather than obscuring, the camera as an essentially mechanical and technological tool. Also referred to as Modernist Photography, this approach abandoned the Pictorialist mode that had dominated the medium for over 50 years throughout the United States, Latin America, Africa, and Europe. Critic Sadakichi Hartmann’s 1904 “Plea for a Straight Photography” heralded this new approach, rejecting the artistic manipulations, soft focus, and painterly quality of Pictorialism and praising the straightforward, unadulterated images of modern life in the work of artists such as Alfred Stieglitz. Innovators like Paul Strand and Edward Weston would further expand the artistic capabilities and techniques of photography, helping to establish it as an independent art form.

Bibliography

Research Websites Accessed 25/11/19

https://www.tate.org.uk/art/art-terms/p/photography/a-z

https://www.theartstory.org/movement/modern-photography/

https://www.artsy.net/gene/modern-photography

https://www.rem.routledge.com/articles/overview/photography

https://ashleighberryman.wordpress.com/2011/01/31/what-is-modernism/

Siegfried Kracauer (1889 – 1966)

According to Wikipedia Kracauer was a German writer, journalist, sociologist, cultural critic, and film theorist. He has sometimes been associated with the Frankfurt School of critical theory. He is notable for arguing that realism is the most important function of cinema.

Siegfried Kracauer’s theories on memory revolved around the idea that memory was under threat and was being challenged by modern forms of technology. His most often cited example was the comparison of memory to photography. The reason for this comparison was that photography, in theory, replicates some of the tasks currently done by memory.

The differences in the functions of memory and the functions of photography, according to Kracauer, is that photography creates one fixed moment in time whereas memory itself is not beholden to a singular instance. Photography is capable of capturing the physicality of a particular moment, but it removes any depth or emotion that might otherwise be associated with the memory. In essence, photography cannot create a memory, but rather, it can create an artifact. Memory, on the other hand, is not beholden to one particular moment of time, nor is it purposefully created. Memories are impressions upon a person that they can recall due to the significance of the event or moment.

Photography can also work to record time in a linear way, and Kracauer even hints that floods of photographs ward off death by creating a sort of permanence. However, photography also excludes the essence of a person, and over time photographs lose meaning and become a “heap of details.” This isn’t to say that Kracauer felt that photography has no use for memory, it is simply that he felt that photography held more potential for historical memory than for personal memory. Photography allows for a depth of detail that can be to the advantage of a collective memory, such as how a city or town once appeared because those aspects can be forgotten or overridden throughout time as the physical landscape of the area changes.

Bibliography

Research Websites Accessed 25/11/19

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Siegfried_Kracauer

https://www.thenation.com/article/trembling-upper-world-siegfried-kracauer/

Read Walter Benjamin’s essay ‘The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction’ in Evans & Hall (1999) Visual Culture: The Reader (also available online). What do you think about Benjamin’s viewpoint? And Kracauer’s?

I found the following points interesting from the essay by Walter Benjamin:

- Benjamin states that man-made artefacts can and have been copied throughout history, however with the introduction of mechanical technology these copies represented something new (p.72);

- Benjamin highlights the fact that it wasn’t until the 1900’s that technical reproduction had reached a sufficient standard that allowed it to ‘reproduce all transmitted works of art and thus to cause the most profound change in their impact upon the public; it also had captured a place of its own among the artistic processes’ (p.73) The implication of which was that photography was finally being considered a form of art worth considering;

- Even though the mechanical reproduction is perfect it lacks the ‘presence in time and space’ (p.73);

- Benjamin discusses the fact that the use of the camera reveal’s what can’t be seen with the human eye as it ‘captured a place of its own among the artistic processes’ (p.73), by adjusting the lens different angles of view can be obtained and change alters the perceptive. The use of slow or log exposures can capture items what is not visible to the eye. The use Raw files enables of the artist reproduce limitlessly but can also mean a loss of ownership;

- The essay argues that the use of technical reproduction can place a copy of the original art in the hands of the masses, a case that would not normally be an option due to cost. ‘Technical reproduction can put the copy of the original into situations which would be out of reach for the original itself’ (p.74);

- Benjamin discusses the position that the value of art is due to its ‘aura’ and or the fact that it has been included in an exhibition. Benjamin states that this aura is related to its ‘ritualistic function’ (p.78) or in some cases its cult value; religious or magical icons which are stored in places of worship – ‘one may assume that what mattered was their existence, not their being on view’ (p.76).

Other Modernist Photographers

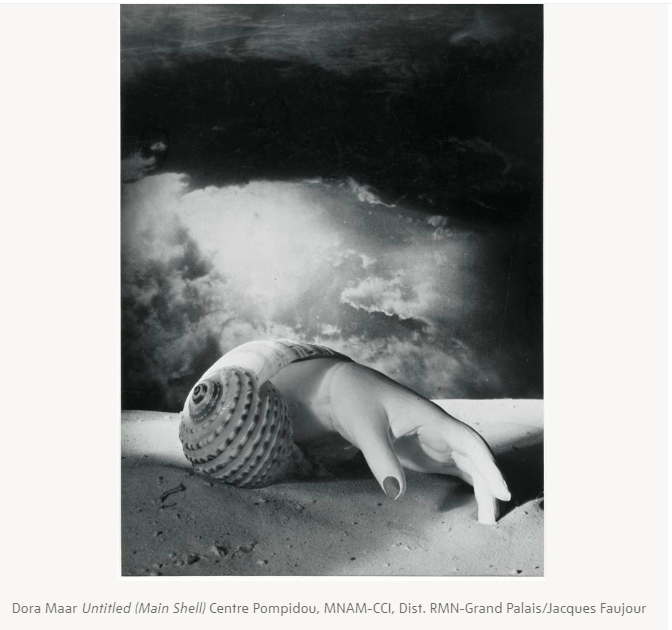

Dora Maar (1907 – 1997)

https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artists/dora-maar-15766

(assessed 25/11/19)

Dora Maar was a twentieth century photographer and painter. She worked across art genres and techniques including photomontage, darkroom experiments and abstract landscape paintings. During the 1930s, she built a successful career as a photographer in fashion and advertising, and travelled to Europe to document harsh social conditions. Her surrealist photographs, collages and photomontages made her one of the few photographers to be included in surrealist exhibitions. Her political beliefs had brought her close to the movement.

In late 1935 or early 1936, Maar met Pablo Picasso. Their relationship had a huge effect on both their careers. Maar documented the creation of Picasso’s most political work, Guernica 1937, encouraged his political awareness and educated him in cliché verre, a technique combining photography and printmaking. Picasso painted Maar in numerous portraits, including Weeping Woman 1937 and encouraged her to return to painting.

By 1939 Maar had withdrawn from photography to concentrate on painting. These often reflect her environment. In Paris during the Occupation, she made still life’s with sombre colour palettes. In the south of France, her landscapes became more abstract. Maar returned to the darkroom in her seventies, experimenting with hundreds of photograms (camera-less photographs). Maar died on July 16, 1997, at 89 years old. Throughout her life she created a vast and varied range of work, much of which was only discovered after her death.

Paul Strand (1890 – 1976)

https://www.theartstory.org/artist/strand-paul/

Site accessed 25/11/19

This is one of the most important photographs in establishing Modern Photography and a noted early street photograph. Strand said that the woman’s “absolutely unforgettable and noble face,” prompted the photograph which is in direct contrast to the formal, posed studio portraits of the period. One of a series of street portraits using a handheld camera with a false brass lens attached to its side, so the subject would be unaware, Strand’s street photographs were influenced by his teacher and mentor, Lewis Hyde, who pioneered social documentary photography for purposes of social reform.

The piece combines this focus on social documentation with a modernist aesthetic which highlights pattern and form, with the diagonal lines of the rectangular blocks mirroring the woman’s gaze and framing the image. The viewer is immediately aware of the contradiction between her dignified face and the oval peddler’s badge (required by law) and the simple and bold sign announcing her disability. As the curator Peter Barberie notes of Strand, “For him, the camera was a machine – a modern machine… He was preoccupied with the question of how modern art – whether it’s photography or not – could contain all of the humanity that you see in the Western artistic traditions.” Blind was published in a 1917 issue of Camera Work and immediately took on an iconic status within the new American photography movement.

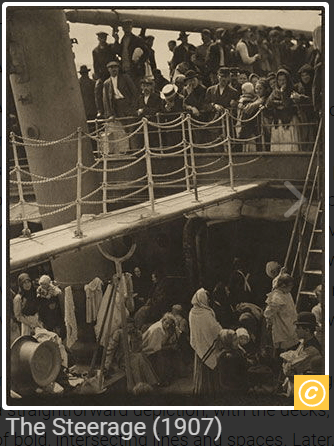

Alfred Stieglitz (1864 – 1946)

Photographer, art dealer and publisher, Alfred Stieglitz is credited as one of the leaders of American modern photography in the early twentieth century. Revolutionary in his portrayal of still life and technical mastery of tone, Stieglitz called for photography’s acceptance as an art form, as well as introducing avant-garde European artists such as Pablo Picasso, Constantin Brâncuși and Francis Picabia to America’s art scene. Influenced by new developments in art, Stieglitz moved away from a more decorative, soft-edged ‘pictorialist’ style. His work The Steerage 1907, with its sharp focus and striking angles is often considered as a benchmark for the beginnings of modernist photography.

Stieglitz promoted this photograph as his first truly “modernist photograph” and it is this image that marks his departure from the Pictorialist style and his abandonment of the idea that photographs should imitate paintings. The photograph depicts steerage (lower class) passengers aboard a ship sailing from New York to Europe, which Stieglitz was also travelling on. The majority of those shown are likely to have been skilled migrant workers who had entered the US on temporary visas to work in the construction industry and were now returning home. It was probably taken whilst anchored at Plymouth, England and was developed in Paris some days later.

In the photograph, Stieglitz creates an image that is as much a study in line and form as a straightforward depiction, with the decks, passageways, and ladders creating a series of bold, intersecting lines and spaces. Later, Stieglitz stated of the image that “I saw shapes related to each other. I saw a picture of shapes and underlying that, the feeling I had about life”. Due to this emphasis of geometric shapes the photograph has been cited as one of the first proto-Cubist works of art.

Although taken in 1907, Stieglitz did not immediately see the potential of the work. He later realized its importance and published it in Camera Work in 1911 in a special issue devoted to his own art and its modernist focus. In the issue he also included a Cubist drawing by Picasso, drawing his own parallels between the two and arguing that the photograph as a medium could be as innovative and as modern, as any work of avant-garde art. Picasso himself also acknowledged the similarities, noting that “this photographer is working in the same spirit as I am”. Photogravure – Museum of Modern Art, New York.