Read ‘Photography’ (Chapter 2) in Howells, R. (2011) Visual Culture on the OCA student website. Note down your own response to Howells’ arguments.

The chapter starts by tracing the history of photography and the development of the daguerreotype. Developed by Louis Daguerre, this enable the first commercial photographers to produce images however had its drawbacks with the fact that they were expensive and only a single application but it ‘was like owning a little piece of reality’ (Howells p.185). The ability to mechanically reproduce an image only came with the development of Henry Fox Talbot’s calotype. This positive-negative process enabled multiple copies to be made and accessible to the general public.

Howells states that Hippolyte Bayard allegedly discovered photography before both Talbot and Daguerre but was prevented from making this public by the French Government as they had previously paid Daguerre. In probably one of the first acts of creative use of photography Bayard produced his image ‘Self Portrait of a Drowned Man (1840). This could arguably be one of the first cases of public duplicity in the world of photography.

As the processes improved photography began to open up a new visual world where people were able to see places and people, they would not be able to do otherwise. Photographs offered an authenticity that was seen to be lacking in fine art. Photography began to be used to record battles and army life and began to show the reality of war ‘were conditions that the well-to-do would never have seen until photography provided them with the visual evidence (Howells p.190). Unlike paintings which are very much the artists interpretation ‘the photograph, it was believed could now show people as they really were’ (Howells p.189).

The camera at the time was thought to be an instrument that was not capable of deceit ‘it can only record the truth’ (Howells p.190). Howells details photography’s umbilical relationship with reality when he states (p.190):

‘Photography, indeed, had a special relationship with reality, which persuaded people that when they looked at a photograph, they were looking at reality itself. They could say, ‘this is Abraham Lincoln’, when actually they were looking not at the man but at a photograph’ and

‘ … an attitude that suggests that a photograph is an unmediated medium with a direct, uncomplicated authenticity and which provides straightforward evidence of the thing photographed. As it is a mechanical recording device, it can only record the truth’.

Eastman’s invention of the Kodak camera in the 1880’s ensured that photography and image production was easily accessible. The use of roll film and the portable camera enabled the user to capture the moment and to react quickly ‘to the things they saw rather than construct them’ (Howells p.186).

The main purpose of Howell’s discuss seems to be based around proving the misconception of Scruton’s argument that photography cannot be art. That a beautiful photograph may not be of a beautiful object or location. That the process of taking an image is not simply about pressing a shutter but the final act of a number of selective choices, which Howells asserts are the creative choices, that ultimately affect the form of the final image. In arguing the case for the possibility of recognising beauty in form rather than content, Howells reminds us that we ‘respond to Impressionist paintings as a result of our fascination with water lilies or haystacks, but because of our emotional response to form’. (Howells p 193-4).

Within the chapter Howells refers to the work by Roger Fry who argues that the subject matter should be demoted and in fact when we look at an image, we should in fact concentrate on the elements of the design, many of which could apply equally to photography as they do in painting. Howells highlights other subject matter experts such as Aaron Siskind and Nathan Lyons. Siskind contended that ‘…the meaning should be in the photograph and not the subject photographed’. Howells refers to some of Siskind’s abstract work of graffiti, battered enamel signs and peeling posters to illustrate his point. Howells (p.195):

‘Siskind began very much in the documentary tradition in the 1930s, when he was a member of the socially committed Film and Photo League in New York. He joined them in documenting topics such as life in Harlem and the Bowery, but he became increasingly interested in the formal properties of photographs as opposed to their subject-matter’.

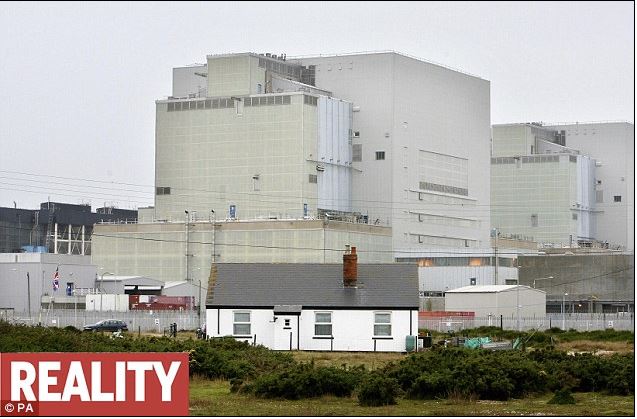

However, Howells points out that with use of clever framing and cropping, a photographer can deliberately make a scene look the way the photographer wants it to. He uses the example of a cottage that was photographed for a real estate magazine, omitting the nuclear power station less than 100 metres away:

Original image taken from a particular angle:[ https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/newstopics/howaboutthat/6243444/House-for-sale-with-views-of-nuclear-power-station.html [Accessed 15/12/19]

Fact:

Howells points out that even one of the most iconic images is not as clean as it makes out and the work of the American Farm Services Administration the Migrant Mother (1936) was altered. These images were produced to create support of the change to economic policies and were made with conscious authorial intent ‘documentary photographers….have something to say, and they want people to react to the photographs they produce’ (Howells p.196). I would argue that the image should be a correct representation. Howells quotes Susan Sontag who wrote in On Photography that photographs are as much an interpretation of the world as paintings are.

To conclude the chapter Howells details the debate about Scruton’s philosophy by William King and Nigel Warburton. King’s analysis of Scruton’s position questions why we look at photographs. King uses the responses given in a survey:

- Interested in the main subject

- The emotional response

- Technical

- Light and/or colour

- Something unquantified that is not the subject matter

The first four points agree or uphold the Scruton view but the last does not. The work by Nigel Warburton claims that the King’s argument is flawed and that Scruton is concerned with archetypical photography.

Finally, Howells concludes that, if photography is to be regarded as art then much depends on a photographer having a style and this is often not clear from one single image, but through a series of images.